To Remember or Not Remember

I’ve had a lot of reasons to think about the concept of memory this year. First disclaimer: my memory isn’t perfect. Nobody’s is. And especially short-term memory as we get older—what did I have for dinner last night; what was the name of that actress who was so compelling in that film?

Second disclaimer: my long-term memory isn’t always perfect either. Between the ages of 12-14 I experienced a series of cataclysmic events. A baby brother who didn’t survive his birth. My biological father dead of cancer at age 36. The car that I was T-boned in on a country road in the mountains at midnight. Reconstructive surgery, and then an emergency appendectomy. And my miracle baby sister was born. Is that the order in which those events happened? Maybe. Certainly I believed that I would NEVER forget how they unfolded. But now, while I remember the events in detail, the order is fuzzy.

So. Not perfect. But.

Ever since college, friends have commented on my ability to remember things. Here’s an exchange between two friends that I recount in my book Our Song: a Memoir of Love and Race, when I couldn’t recall why one of us wasn’t at a weekend event:

“What, Lynda doesn’t remember?” Hannah teased. “You remember everything, even when it’s not about you. Your brain is like our personal diary.”

“Yeah,” Colleen added. “I wouldn’t remember half of high school if it wasn’t for her.”

That conversation took place 50 years ago. How can one remember minute details, including verbatim conversations, that long after they occurred?

I never read a book on how the brain remembers. I never took a memory improvement workshop, nor do I do exercises such as crossword puzzles that rely on recall. What I do just seems to come naturally to me: I simply call up the past. Probably more than most, and possibly more than I should. There’s a popular quote attributed to Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu that says anxiety comes from living in the future and depression from living in the past. I can’t completely disagree. But I just cannot imagine a life devoid of deep remembering—reliving, making sense of, and learning from my story.

There are historical events, life passages, music and books I loved. More often it’s interpersonal relationships, what got said and done, and how it made me feel. That means the memories can be thrilling. They can also bring deep anguish. But I don’t censor them. The happy memories made me fuller. The sad ones, stronger. All of it the complex universe that comprises me, and each of us.

A bit of simplified science: when we remember something, we strengthen that synaptic connection in the brain. Meaning the space between two nerve cells that allows a message to transmit. Each time we do it, the connection gets stronger, like a rut in a road that gets deeper every time the rain finds it. We may not remember dinner because we barely gave it a thought after eating it. But the car accident I was in as a tween? I could tell you every detail—the drive-in movie we’d gone to, when I saw the sports car full of drunk teenagers coming at us, how I felt while waiting for an ambulance, even my outfit that was spattered with blood. That accident changed my life in profound ways. I’ve thought of it countless times.

Something else that helps me remember is going through mementoes from the events of my life. When I wrote my book Our Song, I still had the love letters that were the foundation between me and my long-distance college lover. They served the practical purpose of confirming dates and events. Even more important, his lyrical words took me back to that girl I was then, that boy I loved with all my heart. I laughed, cried and fell in love again while writing it. I wouldn’t trade those memories for anything.

Recently a friend from high school, who happens to be the antagonist in my book, called into question not just my memory but my truthfulness. The heartbreaking story I wrote, of how she went after my college love and convinced him to be insecure about me, she called lies. She even said she threw my book away and dumped leftover food on it (so melodramatic!) But I firmly believe in the truth of the story I told. His old letters bear witness. I have journal entries of interactions between her and me. And I also know that she is a very different type of person from me: she doesn’t like to spend time reviewing the past. ‘On to the next thing’ has always been her motto. Which I find to be a missed opportunity to learn and grow—and sometimes take responsibility for what we’ve done wrong. But that’s how she chooses to live her life. (In my book I cop to the mistakes I made in that debacle, but I admit it took years of soul-searching.)

So, what about you and your memory? Do you live as Lao Tzu suggests, firmly in the present (hard to do)? Spend time in the past like me? Or always look forward like my old friend? And would you like to change? Your history is a precious gift, but you choose whether you keep it wrapped in tissue in the closet, or take it out and gently, thoughtfully unfold the silks and sow’s ears.

By the way, another reason I’m thinking about memory this year is that two close friends of mine have been diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s disease. While I see evidence of cognitive changes, I also see them both connect to our shared histories through music—one by dancing to our old tunes (subtle yet complicated steps that come easier to her than walking), while the other belts out decades of song lyrics with a big grin and nary a mistake. What joy in those!

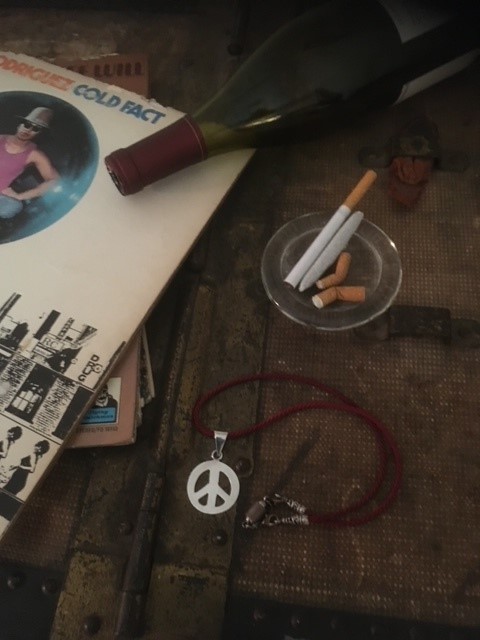

Mementoes from my college years, the era of my book Our Song

I related to this so much because I’ve definitely had a lot of moments where I also second guess my own memories. It’s weird how something can feel so clear in our minds only for us to later realize it might not have really happened that way. This posts really made me think about how much we shape our identities around memories that may not always be as reliable as we think. Very though provoking posts!

It’s true, memory is a quite quixotic phenomenon!

I really enjoyed this reading it points out how often times with memory we remember the things that are most important to us. This can be special because we can hold those memories, regardless of the trauma or bad things we’ve experienced in life.

Very true. And sometimes what we remember is not what was important to someone else. For example, in my book Our Song, I describe (years after the fact) how a friend betrayed me. She accused me of lying! But I have memories and letters. I think she just didn’t want to accept that she had behaved that way.

Thank you for this beautiful and powerful post. As someone just starting college, I’ve been thinking a lot about memory too — what we hold onto, what we forget, and what those choices (or moments of forgetting) say about us. Reading your story made me feel like memory isn’t just something that happens to us — it’s something we participate in, shape, and sometimes even defend.

The way you write about memory feels so alive, especially how you describe the emotional weight certain memories carry. It’s true that some things fade fast, like what we had for dinner, but the events that changed us — the ones that made us feel the deepest pain or joy — those tend to stick. I loved how you explained that remembering is like strengthening a pathway in the brain. That metaphor of the rain carving a rut in the road was such a clear and meaningful way to describe it.

Your honesty about your past — and the fact that some of it is hard to relive — made me think about how memory isn’t just about nostalgia. Sometimes it’s uncomfortable. Sometimes it forces us to face parts of ourselves or our relationships we’d rather avoid. But like you said, those moments can also help us grow. I’m still figuring out how to do that in my own life — how to look back without getting stuck, and how to carry forward the parts that can teach me something.

I was really struck by the part where your old friend dismissed your memories. That must’ve been hurtful, especially since your memories are clearly rooted not just in feeling, but in documentation — letters, journals, reflections. It reminded me that memory is also personal truth. It might not match someone else’s version of the past, but that doesn’t make it any less real. I admire how you stood firm in your truth without needing to erase theirs. That kind of maturity — to honor your own experience while recognizing that not everyone chooses to look back — is something I really respect.

Also, the story about your friends with early Alzheimer’s really touched me. It made me realize how memory can live in our bodies and our senses, even when words and names start to slip away. The fact that your friends can still dance and sing is such a moving reminder that memory isn’t just mental — it’s also emotional, musical, physical. It gave me a new appreciation for the small moments we take for granted.

Personally, I think I’m still learning how to balance the past, present, and future. I tend to reflect a lot, and I sometimes wonder if I do it too much. But after reading this, I feel more okay with that. I think remembering — really remembering — is a way of honoring what’s shaped us, and I hope I never lose that curiosity or that willingness to feel.

Thank you again for sharing such a thoughtful, vulnerable piece. It reminded me that our stories matter — even the painful ones — and that memory, though imperfect, is one of the most powerful tools we have for understanding ourselves and each other.

Wow, Monica – I’m not kidding about you being a reviewer. I could never even describe my own piece in the deep way you have. But I thank you for taking the time to do so. And I commend you for your thoughtful effort to blend past, present and future in your own life. I love this line: I think remembering — really remembering — is a way of honoring what’s shaped us… I say keep remembering and reflecting!